Adoption in the Netherlands

The Netherlands: population 17 million, 41.000 square kilometres, North-West Europe. Adoption: first law on adoption: 1956; ratification of the Hague convention, 1998. (USA April 1, 2008).

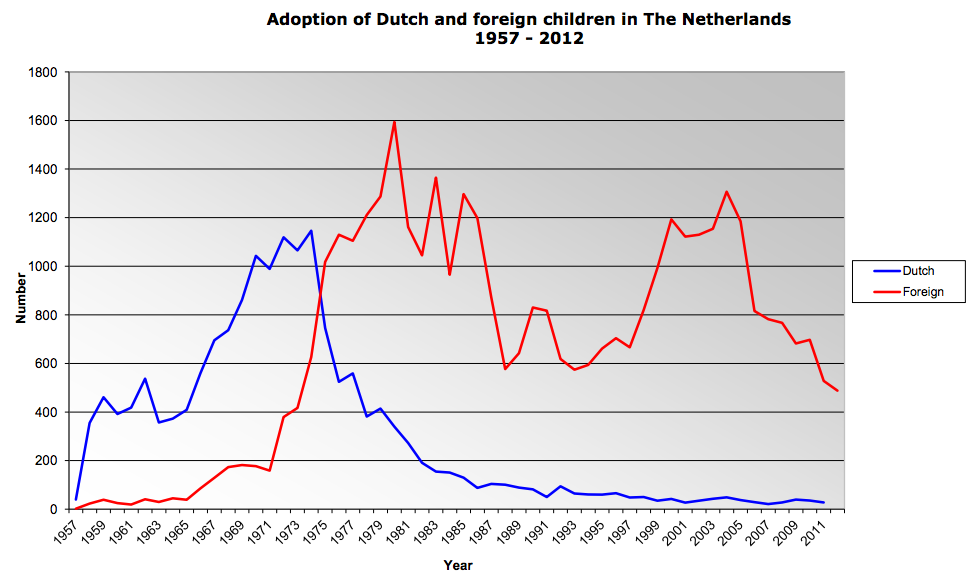

Since 1974 many more foreign than domestic adoptive children in The Netherlands. Since 1990 each year about: 30 to 50 domestic adoptions (mostly from foreign born inhabitants; in 2011: 36) and a flexible number of foreign adoptions. In 1985: 1.297; 1990: 830; 1995: 661; 2000: 1.193; 2006: 816; 2014: 354. In USA in 2004: almost 23.000 children, in 2013 7.092 children. There are quite a few reasons for all these changes in the Netherlands and USA.

Main countries of origin for The Netherlands in 2012 were: China (192; till 2012 6.415), USA (48; till 2012: 471), and from several countries in Africa 135 ( till 2012: 2.195; Ethiopia: 1.112). Important countries in former years: South Korea (4.147), Sri Lanka (3.412), Indonesia (3.041), Brazil (1.393), Colombia (5.443), and India (3.058).

In 2011: 54% of all children were two years of age and older; 14% five years and older.

About 90% of all aspirant adoptive parents are involuntarily childless.

Adoption Procedure

- Send a letter of request to Minister of Justice

- Since 1990 preparation course for all adoptive parents obligatory, six sessions for 8 couples, costs € 1,595.-

- Home study for all aspirant-adoptive parents by Child Welfare Council. Yearly, 2 to 3% refusals for psychological reasons.

- Application to one of the six by the Ministry of Law recognized Dutch adoption agencies. Adoptions organized by private persons need mediation by one of the recognized adoption agencies. Private adoptions: 25 to 50 yearly.

Waiting time before placement of the child: 3-4 years. Placement of adoptive children older than 2 years has become difficult since more is known about mental problems of adoptive children.

Total costs to adopt a child: around € 15.000 to 40.000.

Until today 38.000 foreign children have been adopted in the Netherlands.

Five generations of adoptive parents

Changes in the attitudes of adoptive parents since 1960 form the core of the analysis in this chapter. Our goal is to highlight five generations of adoptive parents who have emerged over time. We describe societal dynamics that have shaped these ‘different generations’ views of adoption, and the impact of these changes on the adjustment of adoption triad members (i.e., birth parents, adoptive parents, and the adoptee). We argue for a generational interpretation of changes in intercountry and intracountry adoptions A pattern of generations of adoptive parents have emerged.

Sociologists have discussed relationships between- and changes in- generations for a long time. Example is Schelsky’s (1957) “The Skeptic Generation”. A generation is defined as “the grouping of an aggregate of individuals characterized by a specific historical setting and by common characteristics on an individual level (biographical characteristics, value orientations, motives) and on a system level (size, composition, culture, specific organizations, social networks)” (Becker, 1985). A generation of adoptive parents, then, is an aggregate of individuals who adopted at least one nonrelated child during the same historical time frame and who share a number of adoption-related experiences, ideas, attitudes and behaviors. We view the construct of ‘adoptive parent generations’ as a helpful framework to interpret changes in the motivation and value orientations of adoptive parents, their decision to adopt a child, the type of child they adopt, their attitudes and behavior regarding adoption related issues, their coping with adoption, and, ultimately, the outcomes for adoptive family members.

One important theoretical dimension for differentiating between generations of adoptive parents is Kirk’s (1963) concept of rejection or acknowledgment-of-differences attitude (R.D.), or (A.D.) in relation to biological versus adoptive family life. These attitudes form a useful element in distinguishing generations of adoptive parents. Both involve complex patterns of motivations and evaluations of adoptive parenthood and emerge from the strains of the adoptive kinship. Parents who adopt an R.D. attitude tend to minimize or deny the inherent differences in adoptive family life, and try to simulate the biological family as much as possible. Consequently, they avoid discussions about the child’s origins and the circumstances surrounding the relinquishment. Kirk also found that they were less empathic about birth parents, and to engage in fewer discussions with their children about their connection to them.

In contrast, other parents adopt an A.D. attitude, which involves accepting the reality that adoption is inherently a different way of forming a family and is characterized by different types of experiences for both parents and children. Kirk reported that this type of parents more readily acknowledged, and respected the child’s dual connection to two families. They were more empathic about the birth parents’ circumstances and their children’s feelings about their origins. Kirk emphasized that the A.D. pattern of coping lead to better adjustment among members of the adoptive family.

Kirk’s R.D. – A.D. distinction is from the early 1960s and continues to have relevance today, because some parents of domestic and intercountry adopted children still attempt to minimize the differences inherent in the upbringing of their adopted children. Although these parents may acknowledge that integrating an adopted child into their family could pose some problems in the first time after the placement, they also believe that with love and attention, they will be able to overcome these problems and raise the child ‘as if it were their own’. This R.D attitude can easily be maintained as long as the adoptee is young. However, by the time the child enters school, most parents find that the challenges of adoptive family life put a strain on their R.D attitude. Their adoptive children bear with them unanswered questions about their background, and can feel pain and loss about being separated from birth family.

As patterns of coping, R.D and A.D attitudes are part of our analysis of generations of adoptive parents, but we consider other elements as well. The wider cultural and social context, the growing availability of research information about adoption, the changing attitudes of adoption professionals and changing practices of adoption agencies, and the type of children who are available for adoption (e.g., domestic or intercountry) are other variables we take into account when defining the time limits and content characteristics of each generation.

- The existence of at least five generations of adoptive parents is suggested:

- The traditional-closed generation (adoptions between 1950-1970)

- The open-idealistic generation (adoptions between 1970-1981)

- The materialistic-realistic generation (adoptions between 1981- 1991)

- The prepared/optimistic-demanding generation (adoptions between 1991-2000)

- The faced with contradictions generation ( adoptions since 2000)

Our analysis suggests that the emergence of these generations has not occurred by chance but is linked to critical historical circumstances that formed the basis for the reasons and direction for the observed change. Some of these circumstances refer to the society as a whole (e.g., the impact of the ‘cultural revolution’ of the late 1960s on all aspects of social life, including family issues, and ideas about sexuality), while others refer to changes more specific to the adoption community (e.g., greater availability of empirically based knowledge about adoption outcomes).

Our conceptualization of five adoptive parent generations is not meant to imply that the experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior of these groups of parents are completely distinct from one another. In the population of adoptive parents at any one time period, there are characteristics of all generations. However, the analysis leads us to believe that during the time periods specified, the majority of adoptive parents have been characterized by the critical experiences and dominant characteristics and attitudes outlined here. Moreover these experiences, beliefs, and attitudes correspond to changes in the broader societal context related to family life in general and to adoption in particular.

This analysis of adoptive parent generations is based on our knowledge of adoption in The Netherlands, and some European countries. It is possible that this analysis is also valid for other countries and cultures, especially where the nuclear family is dominating.

1. The traditional-closed generation of adoptive parents, adoptions before 1970

Before 1970, relatively little information existed about adoption, and what was available was poorly disseminated. As a result, adoptive parents had little to help them in creating their roles as adoptive mothers and fathers. Five decades ago adoptive parents had to find out themselves how to deal with their role as father/mother. They themselves had to answer and solve the questions and problems regarding the adoption status of their parenthood and the adoption status of the child. There was no cultural script available for adoptive parenthood. Kirk (1985, p. 8-9) referred to this predicament as the “role handicap” of adoptive parents.

In addition, prior to the 1970s, little empirical data existed on the social and individual consequences of adoption on members of the adoption triangle. Moreover, what was available was based largely on clinical case studies offering limited insight into the complex nature of adoptive family dynamics on the reality of relinquishment for birth parents. As a result, adoptive parents often received advice and guidance from professionals that was influenced by social prejudice and stigma associated with out-of-wedlock pregnancy and no normative family life as well as the inherent value placed on genetic-based family relationships. In this context, adoptive parents often felt they had little choice but to minimize the differences of adoptive family life and to adjust to their ‘role handicap’ by adopting an R.D. attitude. They believed this pattern of coping would give the child the best chances for successful integrating into the adoptive family and the surrounding community. As a result, the background of the child that is, the biological parents and extended family and the circumstances of the relinquishment – were considered of little relevance to the adoptive family. When the American Jean Patton (an adoptee herself) published her book “The Adopted Break Silence” in 1954 and when Kirk (1963) published his groundbreaking research on adoptive family dynamics, they were far ahead of their time.

To illustrate these statements we take the adoption practice in the Netherlands before 1970 and use results from Dutch and American research. This first generation of adoptive parents adopted their child between the late 1940s and 1970s. This generation consisted of parents for whom adoption was an alternative means of having a child. Given that their first choice was to have a biological child of their own adoption was viewed as a functional response to the emotionally painful reality of infertility or in some cases to the devastating experience of child death. Adoption was considered primarily as a service for childless couples, a means by which they could satisfy their emotional needs or to cement their marriage (Tizard, 1978). It was less often viewed as a service for homeless children. The main goal of these families was to replicate a birth family (Bussiere, 1998). According to this view, only infertile couples would be offered a child.

Because of the societal stigma associated with out-of-wedlock pregnancy and single parenthood, birth parents seldom were encouraged to keep their child. Agencies routinely emphasized adoption placement as the only sensible solution to the problems confronting the unwed, pregnant woman and her ‘illegitimate’ child. To protect the birth parent from scrutiny of others and to minimize social stigma, agencies routinely engaged in confidential adoption placements. The cardinal principles of adoption practice were confidentiality, secrecy, and anonymity. This generation followed the existing regulations and accepted the ideas, values and norms of the authoritarian and dominating social workers. Protests were unheard of. As soon as the child had been placed into the family the door was often closed to outsiders. Social workers even discouraged contacts with other adoptive parents (Mansvelt, 1967; Reitz & Watson, 1992). The adoptive parents hesitated to ask for help from professionals in child and family care, when family problems eventually developed after the arrival of the adoptee.

This traditional-closed generation was also characterized by defending a conventional family system with internally oriented values. At the extreme this could lead to a socially isolated nuclear family. Adoption had a taboo-character and was in the first place oriented towards the benefits of the parents. Adoption plans were hardly discussed with others, because it was a difficult topic (Mansvelt, 1967; Kirk, 1985). Unmarried biological mothers were advised to relinquish their baby and were promised secrecy and anonymity. Sometimes they were even told by social workers that they would soon forget the whole affair (Marcus, 1981). Adoptive parents were not given much information concerning the background of the child. If the child had already been given a name, the new parents often changed this. The prevailing wisdom was that the child should be told about the adoption when it was 4 to 6 years of age, but this fact of life should not be stressed too much. As a matter of fact Kirk’s rejection-of-difference attitude (R.D.) was recommended to adoptive parents. Because the adoptive parents and the adoptee were of the same race, the adoption could be kept secret for both the child and the social surroundings.

The children were mainly, 90%, from unmarried young girls; 5% from married couples, the husband did not accept the child, as he was not the biological father. And from 5% of the couples were taking away of their parental rights.

2. The second generation: the open and idealistic adoptive parent (1970-1981)

Beginning in the mid-1970s, intracountry adoption began to decline in both Western and Northern European countries as well as in the USA and Canada. The greater availability of birth control and abortion, coupled with the growing societal acceptance of single parenthood resulted in the number of infants available for adoption. These changes affected adoptive parents as well and constituted the second generation. Probably the increasing trend towards individualism caused a decrease in the importance of common opinions about the nuclear family and the relationship between mother and child.

As a matter of fact from the 70s on most children adopted by Europeans and Americans were racially different from their adoptive parents. This made the R.D. attitude less easy to maintain. The emerging trend of adoptions in USA was from the 70s on primarily interracial (Feigelman & Silverman, 1983; Federici, 1998).

This second generation was especially open for intercountry/interracial adoption and this continued.

In Western Europe intercountry adoption started slowly in the sixties of last century, and is since the mid 1970s almost the only road to the adoption of young children. This simple fact fitted well into attitudes of the second open and idealistic generation. In Western Europe in the early 1980s about 10.000 intercountry adoptions took place annually. In the mid 1980s this number was decreasing and in the second half of the 1990s there was some increase due to the large numbers of children adopted from China. It seems that Sweden (rate: 9, 4), Denmark (8, 5) and Norway (11, 0) have the highest “rates” of intercountry adoption per 1.000 live births. These rates are for the Netherlands 3,7 and USA 2,0 (Selman, 2000).

In the late sixties and seventies, cultural values and norms changed, starting with the student revolt in Paris (1968) and spreading over North Western Europe. Students and laborers rebelled against authority and the establishment. Existing attitudes, beliefs, and values related to sexuality, woman’s rights, parental authority, governmental control, and religion duties were openly criticized. This ‘Cultural Revolution’ is described as a ‘neoromantic phenomenon’ and had a profound influence on the practice of adoption and ultimately on the second generation of adoptive parents, who, compared to the first generation, were much more open, questioning, and idealistic.

Which social changes are of special importance? The critical changes were the place of women in society, ideas about sexuality and abortion, the decreased influence of religion, authorities and the emergence of the one-parent family. The decreased influence of religion in European countries resulted in generally accepted and performed birth control and family planning. As a result, the birth rate in the Netherlands declined 39% between 1970 and 1975. Furthermore, despite the opposition of the Catholic Church, the use of the pill (from 1961 on) and other forms of contraception became quite common in Europe after 1968. Sex education for young children was also organized in the 1960s, and is now a part of the school curriculum. This ‘cognitive pill’ was perhaps even more effective than the contraceptive pill. The ready availability of contraception, the growing societal support for sex education, and the more open attitude toward sexual behavior in the Netherlands contributed to the fact that the number of teenage pregnancies and abortions among the original Dutch population was the lowest in the world.

Other important changes went together with the advent of television and the information given about the misery in the Third World, the growing mobility of mankind. We elaborate upon the change in emphasis on the influence of nurture over that of nature. Adoptive parents thought that the way of upbringing was more influential than the (genetic) background of their adoptive child. The supposition was confirmed that the R.D. attitude was no longer dominant. The A.D. attitude was prevailing among parents of children adopted interracially in 1970 and onwards.

We replicated Kirk’s investigation with data from 87 Dutch parents (response 93%) who adopted a child from Thailand 1974-1979 (Hoksbergen, Juffer & Waardenburg, 1986). In Kirk’s group the mode (31%) lies at 0 yes responses and in our data at 4 yes responses (29%). In our group there are only two 0 answers i.e. (see table 1).

These changes in attitudes can also be seen in other European countries and USA (Altstein & Simon, 1991; Andersson, 1991; Brodzinsky, 1990). The confidence in the forces of nurture supported the opinion that negative effects of social class differences, for instance on the level of school participation, could be conquered by programs.

Adoption agencies are also sensitive for the changes in norms and values in society. These agencies influence in their turn the practice of parents. For the field of adoption, the important change was the greater openness about intimate subjects. Sexuality, homosexuality, transsexuality, problems with fertility, marriage problems, the effects of relinquishment for biological parents and those of adoption for adoptees became subjects of a public discussion and not only for educated elite. The belief that nurture (of adoptive parents) could conquer nature in developing the personality was crucial. One result was that adoption lost its taboo character. Many began to deem adoption to be a positive solution to infertility, and as an acceptable way to start or enlarge the family. This new view of adoption meant that adoption was seen as a form of childcare; a way of rearing children whose biological family could not, or would not look after them. This new view elicited to conceive adoption as a social accepted way of forming a family. We see three effects as a result of these changes in society:

- Many more couples, including fertile couples, wish to adopt a child. Most countries accept fertile couples as being suitable adoptive parents.

- Relinquishment of a child is no longer socially accepted in Western countries.

- Following from the first two effects intercountry and interracial adoption became an obvious, though not uncriticized result.

This second generation of adoptive parents was more willing to tell their children about adoption, and to share important facts about their background. Discussing the background and the biological parents became less stressful for more and more adoptive parents. However, there was not yet general acceptance of open adoption placements, as was later seen especially in the United States (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998). Sometimes even, candidate adoptive parents preferred a foreign child, because in that case it would be very hard for biological parents to turn up. So, parts of the internal oriented values of the traditional-closed generation, we still see in this generation as well.

The social and cultural climate of society was in these first years of intercountry/interracial adoption ready for changes in ideas about child welfare in the adoption field. Bureaucracy had to accept these changes and to prevent maladjustments, like inappropriate new laws and inadequate new procedures. In most Western countries intercountry adoption became an important way of building up a family.

How did this important change in the adoption field become possible? During this period the official regulations were greatly improved and the media, especially television, presented intercountry adoption as ‘help for children in need’. Adoption was recommended as a last possibility for these children to survive and develop normally. As a result, politicians and authorities could not lag behind, so formal barriers were leveled. Moreover, the results of research, thus far, encouraged intercountry adoption.

Research conducted around and prior to 1980 in the field of adoption, was aimed at evaluating the interracial family (Hoksbergen, 1982; Weyer, 1979; Feigelman & Silverman, 1983). While these studies were rather general and descriptive, the evaluations were positive. For example, one of the conclusions of Feigelman and Silverman (1983, p. 239) in their large study on interracial – Black (n = 58), Colombian (n = 46) and South-Korean n = 298) – adoptions, was: “… our evidence indicates that whatever problems may be generated by interracial adoption, the benefits to the child outweigh the costs. There is no evidence that any of the serious problems of adjustment or racial self-esteem suggested by the critics of interracial adoption are present in any meaningful proportion of non-white children who have been adopted by white parents”.

The open-idealistic generation of adoptive parents had few doubts about their motives for adoption. They maintained highly optimistic expectations that they could overcome whatever obstacle they faced associated with interracial placements, older child placements, and/or effects of early adverse social conditions. However, there was no clear information about possibly burden of upbringing in relation to the age of arrival in the adoption family, and effects of neglect and abuse. One of the consequences of this open attitude toward children in need was a great willingness to adopt older and handicapped children, the so-called “hard-to-place children”. Particularly fertile couples were willing to do so.

This openness towards intercountry adoption, the idealistic motives and the newness of the phenomenon went, however, together with unrealistic expectations about their child. Adoptive parents did not at all expect complex psychosocial problems of their adoptive child. And, the adoption agencies did not prepare them or help them later on with these difficult issues. For adoptive parents proper preparation and after care did not exist. The adoption organizations were new as well, and not too much knowledge-ridden.

The adoptive couples were of middle and upper-middle class (Hoksbergen, 1982; Feigelman & Silverman, 1983; Verhulst & Versluis-den Bieman, 1989). They were financially able to help children and wanted to mitigate the problem of the poverty in the Third World. Their motives for adoption were externally oriented, being strongly influenced by factors coming from outside the family. As a result of their idealism millions of dollars, collected by adoption agencies, were sent to Asia and South America. Compared to the views of the first generation, the attitude of the second generation toward adoption can be mainly characterized as an Acknowledgment-of-Difference (A.D.) attitude.

The open idealistic period including the different attitude towards sexuality was also accompanied by increasing divorce rates. So many children lived with only one biological parent. This was not considered as a risk factor for the growing child.

At the end of this period another side of adoption became slowly apparent. Adoption professionals, researchers and more and more adoptive parents started to realize that for many families intercountry adoption was accompanied with profound psychosocial problems in the family. An important consequence of the increased awareness that adoption of an intercountry child might lead to intense family problems, has been a large change in the composition of the group of adoptive parents, culminating in what we call the third adoption generation, the materialistic-realistic generation.

3. The third generation: the materialistic-realistic generation (1981 – 1991)

Research and clinical practice in many countries made clear that adoptive families were facing intense psychological and emotional problems (Brodzinsky & Schechter, 1990; Hoksbergen et al., 1988; Verhulst & Versluis-den Bieman, 1989; Verrier, 1993; Hoksbergen, 1997; Hoksbergen et al., 2002). It was found that the older the child was at placement, the greater the probability that the child would exhibit behavioral problems later. Since the mid 1980’s we see an increasing controversy concerning the problematic aspects of intercountry adoption. Hoksbergen and colleagues (1988) revealed, using data from 670 institutions (response rate 93%) that in the Netherlands a relatively large number of intercountry adoptees were placed in residential care (349 adoptees, i.e. 5% to 6% of all intercountry adoptees were treated in residential care). This percentage was five times the rate for Dutch-born children.

From 1984 to 1987 psychological problems of intercountry adoptees were an important topic for radio- and television programs. As a result the idealism and high expectations, characteristics of (upper) middle class families, were followed by much disappointment. As a consequence adoptive parents, facing these psychological problems with their adoptive child, felt the need to organize themselves. They realized that adoption professionals and service providers did not take their problems seriously. These parents felt a great need for more professionalization of the psychological services available. Television and press informed the public of accounts of their experiences. In addition, a few biographies of adoptive mothers made it perfectly clear that there was a dark side to intercountry adoption as well.

In the society in general, a more pragmatic generation has emerged. The romantic period has come to an end, and the third generation of (candidate) adoptive parents judged their adoption plans in a more realistic way. The agencies informed the parents about the risks of adopting a child. The professionals used other constructs to describe the conditions of the adoptees. They referred to ‘risk factors’, especially in children adopted at an age of more than two years, because of results of research, attention of the media, and changing psychological ideas about adoption of foreign children (Hoksbergen, Spaan & Waardenburg, 1988) The risk factors of adoption were more emphasized and agencies and professional caretakers were required to give specific help.

In addition to the need of more professionalization of the help, there was a need for better international rules and international understanding for intercountry adoption. The enthusiasm of the pioneers, most of them adoptive parent themselves, sometimes led to carelessness. Other parents, tired of long waiting lists and bureaucracy, managed to get a foreign child on their own without looking too closely at official procedures, laws and the amounts of money requested by lawyers and other mediators in the Third World.

The third generation had much more scientific and clinical information at its disposal. The adoptive parents came to know much about adjustment problems of children adopted from abroad. They were also confronted with the need of their adopted child, an adolescent or adult now, to search for their background. Many want to visit the country of origin and to search for their biological parents. As a consequence, the perspective on intercountry adoption became more realistic, and less idealistic. The expectations of the parents became more in line with the reality of the children with a difficult background, and were less romantic than those of the open idealistic generation of adoptive parents. At least in the Netherlands, their idealism and interest in the poverty in the Third World have decreased as well, possibly as a consequence of a more materialistic and individualistic attitude. In European countries the number of applicants for adoption has dropped. In the Netherlands since 1985 this drop was dramatic. In 1990 it was less than 50% of the number in 1979. In Sweden since 1986 the number of adoptions has constantly decreased.

According to the Dutch adoption agencies it has become more difficult to find families for adoptive children with special needs and older children. In the USA the same difficulty in placing older children was met, but at the same time however, more older children than ever were adopted, partly because the decreasing number of infants. There are even special adoption organizations with programs to expand the number of families willing to accept a special needs child. Exact statistics about numbers of adoptions in relation to the age of arrival in USA do not exist, however.

The realistic approach to adoption had another effect. Less fertile couples were willing to adopt. In Sweden, in the seventies, among the families having adopted through the two main organizations some 20% had biological children (Johansson, 1976). This percentage is now about 12%. In The Netherlands in 1980, 32% of the adoptive parents had one or more biological children; in 1993 this was 23% (CBS, 2003). This realistic generation contributed to increasing wealth in Europe and the USA. A new generation that experienced that wealth is just available or at least within reach, and that we all are entitled to live in wealthy conditions emerged. This is the fourth generation.

4. The fourth, the optimistic-demanding generation – adoptions since 1991

Since the mid of the nineties we notice in all Western countries an increase in the number of intercountry adoptions, first slowly but last years spectacularly (Selman, 2000). In the Netherlands, for example, the number of adoption requests by candidate adoptive parents in 2002 was with 3049 approaching the top year of the second generation, 1979: 3388 (Hoksbergen, 2001). We assume that this increase is caused by several changes in society. Firstly, improved economical circumstances make it for more couples possible to pay the high costs of adoption. There is hardly any unemployment, though since 2002 unemployment is growing. Secondly, the still growing trend towards individualism is a main issue. More and more infertile couples seem to “claim a child”. They express some sort of motive to adopt, as the right to get a child. Modern medical techniques did not help, now adoption should do it. The motive of helping a child in need has become less important.

Important also is the professionalized preparation of candidate adoptive parents (e.g., Bureau Preparation Intercountry Adoption, founded in 1989 in the Netherlands). This preparation course is obliged for all candidate adoptive parents. They have to pay the costs themselves (2013: $ 1595,-).

Adoption of a child from China and Taiwan has become very popular. These are mainly children younger than two years of age (in 2002, 71% of the 510 children; in 2012, 40% of the 229 children).

There is much more knowledge and therefore proper anticipation to possible psychosocial problems in adoptive families. The volume of books and articles about adoption, with useful advices and suggestions is large, and still growing (Brodzinsky, Schechter & Henig, 1992; Hoksbergen, 1996). To be entitled to have a child is reflected in the Netherlands by the possibility to adopt a child as one parent.

This fourth generation of adoptive parents is more internally oriented and less fixated on the best interests of a child in need. Their way of thinking seems to be more in line with the approach of candidate parents of the new technologies of procreation. They show an attitude whether they have ’the right on a child’, no matter how. Using a surrogate mother with donor semen is a sometimes-realized possibility. Thoughts about the future identity problems of the child are postponed or even ignored. Going back to Kirk’s distinction we see partly a return of the R.D. attitude, at least regarding the medical and psychosocial situation of the child. The adoptive child should be as young and as healthy as possible. Adoption agencies are explicitly confronted with demands on age at placement, and parents are less willing to accept a medical risk of the child. Often candidate parents require an adoptive child younger than two years of age. It has become difficult to place children of four years and older. During the period of the second and third generation ‘old’ was defined at six years and older; it is changed in: two years and older. Earlier it was almost always possible to find a home for an adoptive child, this is no longer the case in the Netherlands. The idealistic motive to adopt a ‘child in need’ has got much less importance.

The fourth generation seems also rather optimistic about their educational possibilities of young adopted children. However, from research we know that experiences in the country of origin are of much more importance than the age at placement as such. A history of neglect at the age of 12 months is more risky for the development of several behavioral disorders than the age at placement of for instance three years with, on the contrary, a healthy background (Hoksbergen et al., 1999; Verhulst, Althaus & Versluis-den Bieman, 1992).

5. The generation faced with contradictions (adoptions since 2000)

The last generation is again faced with scandals. Child abuse, selling of children (Gibbons & Rotabi, 2012), some biological parents still wrongly informed about the meaning of adoption, too much money involved etc. On the other hand we see the situation of children in need asking for a healthy life in a suitable family. The adopted children are more and more fysically or mentally handicapted. The sending countries are not able to find any parents available for these children.

For adoptive parents the contradiction is clear. On the one hand hesitations about the correctness of procedures and the methods and policy of the adoptionagencies. Are the children offered for intercountry adoption really adoptable according to standards of the receiving countries? On the other hand poor children in need, often in one way or the other handicapped. The effect is that there are less and less adoptive parents. In the Netherlands the number of adoptive parents has dramatically fallen down. Since 2004 from 1307 to 488 in 2012. In the USA we almost see the same changes in the adoption figures. Another factor to understand this decrease is of course the economic crisis.

Concluding statements and future direction

Modern adoption can be understood as firmly connected to the evolving changes in the culture and the structure of society. From the ninety sixties until now five generations can be distinguished. The first just formed a family, and it was considered as a pity that adoption had to be a part of it. The second was idealistic and romantic in helping countries and children in need. The third generation was more sophisticated. It was a realistic generation, realistic about the psychosocial problems connected with the adoption of foreign children. They live in a world of communication and media that brings all the wars and suffering of children far away, home. This generation lived in growing prosperity and individualism. The fourth generation is accustomed to fulfilling of their (im) material wishes. They feel entitled to have (adoptive) children if they want, and preferably as young and healthy as possible. The fifth is faced with contradictions. On the one hand adoption scandals in quite a few sending countries, on the other hand the need of poor children, most of them with some physical or mental handicap.

The biological family of the adoptee is now much more a part of reality in adoptees’ lives. Adoptive parents are well informed about the necessity of the telling issue and the benefits for the adoptee to know more about his background (Brodzinsky, Schechter & Henig, 1992). Adoptive parents have abundantly the possibility to be familiar with the risks of adoption, but use this information not always. In U.S.A., New Zealand and more slowly in European countries open adoption is increasingly practiced. Unmarried mothers are less stigmatized. Adoption agencies and modern adoptive parents take their grief due to the relinquishment of the child seriously (Pilotti, 1990; Triseliotis, Shireman & Hundleby, 1997; Grotevant & McRoy, 1998).

To be able to understand motives, value orientations and attitudes towards adoption, of adoptive parents, and of society in general, we should be aware of the important demographic, economical and political changes in society. More and more couples have to cope with infertility (Te Velde, 1991). Adoption will be a possibility, when they wish to bring up a child. In Western society intercountry adoption will continue to be important to start a family. Because we know much more about the effects of neglect and abuse, but not so much about ways to overcome and heal these negative effects, we can expect that only a small number of aspirant-adoptive parents are willing to adopt ‘special needs children’.

Changes like the decrease in intracountry adoption, and the replacement of these traditional adoptions by intercountry adoptions and mostly interracial adoptions, can be more easily understood now.

Recently we see (1) a more demanding attitude emerging; (2) a better preparation for their adoption adventure than former generations, (3) together with the large number of Chinese children available for adoption a clear demand for young, healthy, and even intelligent babies, though these healthy children are less and less available, and (4) a dramatic decrease in the number of available adoptive parents.

In coming decades we expect that intercountry adoption in Europe will never again become as popular as it was during the open-idealistic generation. Fewer fertile couples will adopt, and more children, particularly older children, will become increasingly hard-to-place. Modern fertility techniques, such as in vitro fertilization, will become even more significant and will also lead to a decline in the number of parents seeking to adopt children. Couples formerly considered to be infertile will now have more medical procedures available to address their fertility problems and they will make more extensive efforts to have a child of their own.

On the one hand: adoption has become easier: ‘the role handicap’ for adoptive parents is now less salient, given the higher diversity in family arrangements in modern societies, and the fact that adoption has become more visible in these societies. All these factors should facilitate adoptive parenting. Moreover better professional practices are formed and available for adoptive parents and adopted children. On the other hand: adoption may have also become more complicated: the amount of prejudice against foreigners seems to increase.

There is a concern about the hard to place children. The fourth and probably also the fifth generation feels entitled to have a healthy child. To improve adoption of these hard to place children, agencies firstly, can look for families that are able to handle difficulties in upbringing, and secondly they should offer a system of aftercare. They also have to feel the practical and moral obligation to inform the adoptive parents as completely as possible about the background of the adoptee, and reveal the results of the medical en psychological assessment of the adoptee. Adoptive agencies should be certified. More work has to be done in the original countries of the adoptees. It is sometimes suggested to send Western physicians and adoption experts to assess and diagnose the hard to place children. Finally the general public should be informed about the general statistics and results of adoption in each country.

Finally basic research is still needed to better understand how adoptive parents’ expectations, motives and attitudes influence adoption outcomes.

References

Altstein, H. & Simon, R.J., Eds. (1991). Intercountry adoption. A multinational perspective. New York: Praeger.

Andersson, G. (1986). The adopting and the adopted Swedes and their contemporary society. In: R.A.C. Hoksbergen & S.G. Gokhale (Eds.), Adoption in worldwide perspective. A review of programs, policies, and legislation in 14 countries. Lisse: Swets en Zeitlinger.

Anderson, G. (1991). Intercountry adoptions in Sweden – the experience of 25 years and 32,000 placements. Stockholm: Adoption Center.

Becker, H.A. (1985). Dutch Generations Today. Netherlands Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences. Wassenaar: NIA, Paper.

Brodzinsky, A.B. (1990). Surrendering an infant for adoption. In: D.M. Brodzinsky & M.D. Schechter (Eds. 1990). The psychology of adoption. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brodzinsky, D.M. & Schechter, M.D. (Eds. 1990). The psychology of adoption. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brodzinsky, D.M., Schechter M.D. & Henig, R.M. (1992). Being Adopted. The Lifelong Search for Self. New York: Double Day.

Bussiere, A. (1998). The development of adoption law. Adoption Quarterly, 1, 3-25.

Carangelo, L. (1999). Statistics of Adoption. Palm Desert: Americans for Open Records.

CBS (2003). Jaarcijfers Geboorte, Maandstatistiek Bevolking (Year figures, Birth Month statistics of the Population).

Federici, R. (1998). Help for the hopeless child. A guide for families. With special Discussion for Assessing and Treating the Post-institutionalized child. Washington: Federici and Associates.

Feigelman, W. & Silverman, A.R. (1983). Chosen Children: New patterns of adoptive relationships. New York: Praeger.

Gibbons, J.L. & Rotabi, K.S. (2012). Intercountry adoption. Policies, Practices, and Outcomes. Farnham England, Burlington USA: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Grotevant, H.D. & McRoy, R. (1998). Openness in Adoption. Exploring family connections. Thousand Oaks, London: Sage Publications.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. (Ed.), Baarda, B., Bunjes, L.A.C. & Nota, J.A. (1982). Adoptie van kinderen uit verre landen (Adoption of children from far-away countries). Deventer: Van Loghum Slaterus.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C., Juffer, F. & Waardenburg, B.C. (1986). Adoptiekinderen thuis en op school. De integratie na acht jaar van 116 Thaise kinderen in de Nederlandse samenleving (Adoptive children at home and at school. The integration after 8 years of 116 children born in Thailand, in Dutch society). Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C., Spaan, J.J.T.M., & Waardenburg, B.C. (1988). Bittere Ervaringen. Uithuisplaatsing van buitenlandse adoptiekinderen (BitterExperiences. Placement in residential care of foreign adoptees). Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. (1996). Child adoption – A guidebook for Adoptive Parents and their Advisors. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. (1997). Turmoil for Adoptees during their Adolescence? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 20, 1, 33-46.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. en de medewerkers van het Roemenië project (1999). Adoptie van Roemeense kinderen. Ervaringen van ouders die tussen 1990 en medio 1997 een kind uit Roemenië adopteerden(Adoption of Romanian children. Experiences of parents which adopted a child from Romania between 1990 and mid 1997). Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht, afd. Adoptie.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. (2001). Vijftig jaar adoptie in Nederland. Een historisch-statistische beschouwing. (Fifty years of adoption in the Netherlands. A historical-statistical consideration). Utrecht: Department of Adoptiin.

Hoksbergen, R.A.C. en de medewerkers van het Roemenië project (2002). Effecten van verwaarlozing (Effects of neglect). Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht, afd. Adoptie.

Johansson, S. (1976). Tjänstledighet och föräldrapenning för adoptivföräldrar (Vacation and costs for adoptive parents). Sundbyberg: Adoption Center.

Kirk, H.D. (1963). Shared Fate. A Theory and Method of Adoptive Relationships. Port Angeles: Ben-Simon Publications.

Kirk, H.D. (1981, 1985). Adoptive Kinship. A modern institution in need of reform. Port Angeles: Ben-Simon Publications.

Mansvelt, H.F.M. (1967). Adoptief-ouders aan het woord (Adoptive parents speak out). Alphen a.d.Rijn: Samson.

Marcus, C. (1981). Who is my mother? Birth parents, adoptive parents and adoptees talk about living with adoption and the search for lost family. Toronto: Gage Publishing Ltd.

Pilotti, F. (1990). Intercountry adoption: Trends, Issues and Policy Implications of the 90’s. Montevideo: Social Affairs Unit.

Reitz, M. & Watson, K.W. (1992). Adoption and the family system. London, New York: The Guilford Press.

Schelsky, H. (1957). Die skeptische Generation, eine Soziologie der deutschen Jugend. (The sceptic generation, a sociology of the German youth). Düsseldorf: Ullstein.

Selman, P. (Ed., 2000). Intercountry Adoption. Developments, trends and perspectives. London: British Agencies for Adoption and Fostering.

Te Velde (1991). Zwanger worden in de 21ste eeuw: Steeds later, steeds kunstmatiger(Becoming pregnant in the 21st century: Increasingly later, increasingly more artificial). Utrecht, oratie.

Tizard, B. (1978). Adoption a second chance. New York: Free Press.

Triseliotis, J., Shireman, J. & Hundleby, M. (1997). Adoption, theory, policy and practice. London, New York: Cassell.

Verhulst & Versluis-den Bieman (1989). Buitenlandse adoptiekinderen: vaardigheden en probleemgedrag (foreign adoptive children: capacities and problem behavior). Assen: Van Gorcum.

Verhulst, F.C., Althaus, M. & Versluis-den Bieman, H.J.M. (1992). Damaging Backgrounds: Later Adjustment of International Adoptees. Journal American Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 31:3. 518-525.

Verrier, N.N. (1993). The Primal Wound. Understanding the adopted child. Baltimore: Gateway Press.

Weyer, M. (1979). Die Adoption fremdländischer Kinder (Adoption of foreign children). Stuttgart: Quell Verlag.